Research

PFAS Research

Recent findings have demonstrated elevated PFAS levels in agricultural soils across the world due to inadvertent introduction through the application of biosolids, atmospheric deposition and irrigation with contaminated water. The current methods available for PFAS remediation from soil - excavation followed by incineration, are not feasible for wide-scale agricultural usage.

Research on PFAS in agricultural systems is on-going across the world, including at Michigan State University, however there is a shortfall of data in the literature on the bio-accumulation factors, transfer factors, and the health effects on plants and livestock. Because of the nature of PFAS could favor uptake and bioaccumulation in plants and livestock, even low levels of PFAS in the soils or irrigation water could result in elevated concentrations within crops and/or animals.

Crops

As of now, there is limited published data in the scientific literature on PFAS uptake and accumulation in forage plants on farm fields. The majority of the studies on plant uptake of PFAS are limited to common grains and vegetables, and the comparisons are not very among different plant species with varying physiological characteristics. Michigan State University is currently conducting several studies on contaminated farm fields that will provide much needed information on crop uptake of PFAS and their bioaccumulation. Direct consumption of contaminated fruits and vegetables, as well as animal consumption of PFAS-tainted crops represent important exposure pathways for humans to these chemicals.

A paper recently published recently published in The Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry (October 2024) reported that Maine researchers studied the uptake of PFAS by mixed forage species in contaminated fields and found a wide variance in bioaccumulation. The study was conducted in mature perennial forage crops dominated by grasses with varying amounts of legumes within a single farm and between different farms. Interestingly, the variation was not easily explained by plant variety, soil type and properties and PFAS loadings in the soil. This study found that PFOS transfer from soil to forage was significantly greater in the second cuttings. The factors responsible for higher uptake in a second cutting of grass in this study are unclear, though it is thought to be due to a higher proportion of leaf to stem present in the second cutting. Multiple studies have demonstrated that short chain PFAS accumulation tends to be higher in leaves.

Similar to field crops, many studies in vegetables have found higher PFAS accumulation in leaves and stalks than in the edible fruits and seeds. In a study with soils amended with sewage sludge, (Lechner and Knapp, 2011), found higher accumulation of PFOA and PFOS in leaves of carrot, cucumber, and potato, and less amount in the peeled edible parts.

In a study of Minnesota home gardens where PFAS source was detected in the water, floret vegetables had higher concentrations of PFAS than other plant parts and, in general, fruits and seeds tended to have lower concentrations of PFAS than leaves and stems (Scher et al., 2018).

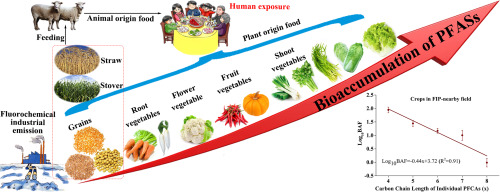

Research conducted at a large fluorochemical manufacturing site in China found that PFAS were bioaccumulated in the all of the vegetable species (10) and three field crops species (corn, wheat and soybeans) produced in nearby highly contaminated agricultural fields. The patterns of PFAS bioaccumulation were different. Grains had the least PFAS accumulation compared to roots, flowers, fruits and shoots.

If you think that your crops may be contaminated with PFAS, please contact Faith Cullens-Nobis at MSU Extension for a confidential discussion about testing and potential mitigation strategies.

Animals

The lifetime health advisory levels for PFAS have not yet been formulated specifically for pets or livestock. While adverse impacts to PFAS exposure have been reported in a large number of studies focused on fish and rodents, the impacts suggest liver disease, thyroid disease, reproductive disease, organ failure and developmental effects. At the moment, there is limited published evidence of adverse health events on livestock. Multiple studies have found PFAS in the serum, liver, kidneys, and milk of production animals, but there is a gap in the understanding of adverse health effects to PFAS exposure in livestock. While these contaminants are considered “forever chemicals” and can stay in your animals a long time, they are not forever in the same concentration in your animals. They can again produce safe food once animals are on non-contaminated feed for an extended period of time.

In Clovis, New Mexico, groundwater that served a large dairy operation was found to be highly contaminated by the use of aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF), which has been commonly used at military sites and airports for suppression of petroleum fire. PFAS levels in cattle plasma were well above what is thought to be safe, yet cattle showed no obvious signs of illness. In this herd, death and culling rates were in line with national averages despite heavy contamination (Lupton, et al, 2022).

In this case, like several other across the country, cows were secreting high concentrations of PFAS into the milk, triggering consumer concerns. Research does suggest PFAS may build up over time in animal tissues and could be present in varying amounts in their meat, milk, and eggs. In many cases, animals put on to clean feed and water have reduced PFAS secretion enough to produce saleable milk or meat, however in others, like the dairy farm in New Mexico, contamination is so high that animals are not able to clear the PFAS from their body and must to be euthanized.

At this time, there is no reliable way to calculate how much PFAS will be transferred from contaminated feed or water into animal products. The present mitigation strategies are to provide animals with PFAS free feed and water or if that is not possible, dilute contaminated feed as much as possible and monitor the animals. Currently there are no federal or state food safety standards for PFAS levels in food. However, in some states like Maine, the Center for Disease Control has set an action level of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) in beef (3.4 ppb) and milk (210 ppt) , which guides the decision to allow a farm’s beef or milk to be sold in the commercial market.

Unfortunately, dealing with highly contaminated carcasses is not an easy task because the PFAS do not easily breakdown, which could lead to contamination of areas where the animals are buried or composted. A recent study from Maine demonstrated that PFAS concentrations actually increased during the composting process, although the pathway is unclear. Landfilling carcasses is a potential option, although the majority of landfills in Michigan will not take livestock contaminated by PFAS. Incineration is another possibility but there are developing guidelines on incineration practices.

If you suspect your animals are contaminated with PFAS, please contact Faith Cullens-Nobis at MSU Extension for confidential discussions on testing and mitigation.

Print

Print Email

Email